Selections for Wednesday, October 8th at 7:30

Neurology

Fiction

How had I never noticed this before? Could it be that the poor little orphan of my memory was harbouring vengeful fantasies? Had I all along been mistaking a gothic character for a Dickensian one? It’s with assumptions such as this that Jean Rhys plays in her fabulously atmospheric exploration of the life of the first Mrs Rochester.

Antoinette Conway is an orphan, too, as a Creole heiress marooned in Jamaica, in the ruins of a slaving culture that has made her a pariah to her black neighbours. When she is a child, the family mansion is torched and a girl whom she wants to be her friend throws a rock at her head – incidents that resound with distorted echoes of Jane Eyre.

There is nothing idyllic about life on this island, and Dominican-born Rhys is brilliant at evoking the swarming oppressiveness of relentless sunshine. Where Brontë’s gothic is cold and dark, Rhys’s sweats and swelters. “I knew the time of day when though it is hot and blue and there are no clouds, the sky can have a very black look,” says Antoinette, who nevertheless finds razor grass, red ants and snakes “better, better than people”.

Into this hallucinatory inversion of an island paradise blunders Edward Rochester, a malarial younger son in search of a fortune, who picks up the narrative in the second section with his own sense of alienation: “Too much blue, too much purple, too much green. The flowers too red, the mountains too high, the hills too near.”

Nonfiction

If you enjoy medical case histories that are sensitive yet lively, weird but informative, then Sacks’ book is your ticket.

A neurologist who writes with wit and zest, he will fascinate you with stories of patients like the man in the title—a professor who couldn’t recognize faces and who patted the tops of fire hydrants believing them to be children. Nietschze asked whether we could do without disease in our lives and the author explores this interesting concept with a rare and invigorating philosophic sense. Sacks is no ordinary practitioner; his patients suffer from rare complaints like Korshakov’s syndrome, Tourette’s and other afflictions, some of which make the patient unsure of the reality of his own body. Their tragedies and their courage are joined with the author’s astute professionalism and humanity to make for a riveting foray into the unknown. The history of these strange cases and the state of the art of medicine are deftly probed. Yet in the midst of all this tragedy, there is an eerie comic quality. Take the 80-year-old ex-prostitute who discovers a new liveliness and euphoria, which she enjoys immensely. However, the reason for this is a recurrence of an old syphilis infection. Does she want to be totally cured and lose this new found ebullience? Not really. She relishes “Cupid’s disease’s” strange excitation of her cerebral cortex too much. To Sacks’ credit, he agrees with her.This book ranks with the very best of its genre. It will inform and entertain anyone, especially those who find medicine an intriguing and mysterious art.

Selections for Wednesday, September 10th at 7:30

Spies

Fiction

Unlike a traditional whodunnit, we’re not being challenged to predict the outcome of the case. (A careful reader, in fact, will notice that Smiley already guesses the identity of the mole at the novel’s outset.) Instead, we’re dropped into a world we barely understand, and our job is to unpack how the individuals populating London Circus align themselves with power. How class and prestige serve to structure and deform social relations. More importantly, what qualities of personality might make someone resistant to the kinds of institutional rot that allow bad actors like Philby—and the coterie of power-hungry flatterers who facilitate his rise to power—to flourish.

Seeing the book this way clarifies why, all those years back, I’d experienced Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy as such a challenge to my half-baked l’art pour l’art convictions, and why I felt I needed to write differently in its aftermath. Le Carré intends the book to confront readers’ complacency. He weaponizes the spy genre as a tool for luring them in, then entraps them and makes them marinate in his pitiless moral vision. It’s a social novel in the guise of genre fiction, and, like all social novels, its métier is political critique. The substance of the critique becomes more explicit in le Carré’s later works—for example The Constant Gardener (2001), in which a crusading activist is murdered by a pharmaceutical company for trying to reveal its program of illegal testing on Kenyan subjects, or A Most Wanted Man (2008), in which an innocent Muslim teenager becomes a pawn in the machinations of competing intelligence services—but in Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy the marriage of plot and meaning, structure and signal, form and substance, is at its most subtle and complete.

Nonfiction

A tale of espionage, alcoholism, bad manners and the chivalrous code of spies—the real world of James Bond, that is, as played out by clerks and not superheroes.

Now pretty well forgotten, Kim Philby (1912-1988) was once a byname for the sort of man who would betray his country for a song. The British intelligence agent was not alone, of course; as practiced true-espionage writer Macintyre (Double Cross: The True Story of the D-Day Spies, 2012, etc.) notes, more than 200 American intelligence agents became Soviet agents during World War II—“Moscow had spies in the treasury, the State Department, the nuclear Manhattan Project, and the OSS”—and the Brits did their best to keep up on their end. Philby may have been an unlikely prospect, given his upper-crust leanings, but a couple of then-fatal flaws involving his sexual orientation and still-fatal addiction to alcohol, to say nothing of his political convictions, put him in Stalin’s camp. Macintyre begins near the end, with a boozy Philby being confronted by a friend in intelligence, fellow MI6 officer Nicholas Elliott, whom he had betrayed; but rather than take Philby to prison or put a bullet in him, by the old-fashioned code, he was essentially allowed to flee to Moscow. Writing in his afterword, John Le Carré recalls asking Elliott, with whom he worked in MI6, about Philby’s deceptions—“it quickly became clear that he wanted to draw me in, to make me marvel…to make me share his awe and frustration at the enormity of what had been done to him.” For all Philby’s charm (“that intoxicating, beguiling, and occasionally lethal English quality”), modern readers will still find it difficult to imagine a world of gentlemanly spy-versus-spy games all these hysterical years later.Gripping and as well-crafted as an episode of Smiley’s People, full of cynical inevitability, secrets, lashings of whiskey and corpses.

Selections for Wednesday, June 11th at 7:30

Persia

Fiction

The novel has the flavor of Ken Follett’s The Pillars of the Earth, but with a deeper character development and story arc. The narrative is fast-paced, one engrossing scene unfolding into another, revealing yet another adventure, danger or discovery. The intensity of Rob’s desire to unearth the secrets of healing is admirable and the portrayal of Bagdad and Persia as the center of advanced medicine is intriguing. It was interesting to see the comparison between the crude monastic treatments practiced in Europe which relied heavily on bleeding versus those practiced by the famed Avicenna in Persia where illnesses were scientifically studied and complex surgeries such as cataract removal were performed. Vivid descriptions permeate throughout the book such that one gets the feeling of actually being in the dusty streets of ancient Isfahan skirting legless beggars and camel dung. An insightful and unforgettable read.

Nonfiction

A myth-shattering view of the Islamic world’s myriad scientific innovations and the role they played in sparking the European Renaissance. Many of the innovations that we think of as hallmarks of Western science had their roots in the Arab world of the middle ages, a period when much of Western Christendom lay in intellectual darkness. Jim al- Khalili, a leading British-Iraqi physicist, resurrects this lost chapter of history, and given current East-West tensions, his book could not be timelier. With transporting detail, al-Khalili places readers in the hothouses of the Arabic Enlightenment, shows how they led to Europe’s cultural awakening, and poses the question: Why did the Islamic world enter its own dark age after such a dazzling flowering?

Selections for Wednesday, May 14th at 7:30

Frederick Douglass

Fiction

TransAtlantic is basically divided into two parts. The first is a triptych of historical figures at key moments in their careers: the aviators John Alcock and Arthur Brown as they make the first transatlantic flight in 1919; Frederick Douglass on his visit to Ireland in 1845-46; and former U.S. Senator George Mitchell, brokering the Good Friday peace agreement in Belfast in 1998. The second half traces four generations of Irish women whose lives intersect in more or less significant ways with those of the flyers, Douglass, and Mitchell.

Nonfiction

The definitive, dramatic biography of the most important African American of the nineteenth century: Frederick Douglass, the escaped slave who became the greatest orator of his day and one of the leading abolitionists and writers of the era.

As a young man Frederick Douglass (1818–1895) escaped from slavery in Baltimore, Maryland. He was fortunate to have been taught to read by his slave owner mistress, and he would go on to become one of the major literary figures of his time. He wrote three versions of his autobiography over the course of his lifetime and published his own newspaper. His very existence gave the lie to slave owners: with dignity and great intelligence he bore witness to the brutality of slavery.

Selections for Wednesday, April 9th at 7:30

Journalists & War

Fiction

Maali, the son of a Sinhalese father and a burgher mother, is an itinerant photographer who loves his trusted Nikon camera; a gambler in high-stakes poker; a gay man and an atheist. And at the start of the novel, he wakes up dead.

He thinks he has swallowed “silly pills” given to him by a friend and is hallucinating. But no: he really is dead, and seemingly locked in an underworld. It’s no Miltonian pandemonium; for him, “the afterlife is a tax office and everyone wants their rebate”. Other souls surround him, with dismembered limbs and blood-stained clothes; and they are incapable of forming an orderly queue to get their forms filled in. Many of the people he meets in this bleakly quotidian landscape are victims of the violence that plagued Sri Lanka in the 80s, including a Tamil university lecturer who was gunned down for criticising militant separatist group the Tamil Tigers. The novel also depicts the victims of Marxist group the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna , or People’s Liberation party, who similarly waged an insurrection against the Sri Lankan government, and killed many leftwing and working-class civilians who got in their way.

Nonfiction

Committed war reporting in mainstream journalism is an endangered species today. That’s not where the money is, or the fashion. There’s hardly anyone around who does it any more, which is why Martha Gellhorn’s reissued war correspondence has such impact and vitality.

She began writing from Spain in 1937. ‘I belonged,’ she comments in a preface, ‘to a Federation of Cassandras,’ using her typewriter to warn the democracies of impending Fascist danger. But ‘In the end we became solitary stretcher-bearers,’ saving whom they could from the flames.

There is a hard, shining, almost cruel honesty to Gellhorn’s work that brings back shellshocked Barcelona, Helsinki, Canton and Bastogne – the prelude and crashing symphony of World War II – with almost unbearable vividness.

At the time Gellhorn ‘was a pacifist and it interfered with my principles to use my eyes’. By 1936 she knew the score and set up shop as an outspoken anti-Fascist Cassandra. Her sympathies always were with the common soldier, the wounded and the young. But she never was woolly or sentimental, and her pieces, almost without exception, stand up extraordinarily well even after almost fifty years.

Selections for Wednesday, March 12th at 7:30

American Dust Bowl

Fiction

Texas, 1934. Millions are out of work and a drought has broken the Great Plains. Farmers are fighting to keep their land and their livelihoods as the crops are failing, the water is drying up, and dust threatens to bury them all. One of the darkest periods of the Great Depression, the Dust Bowl era, has arrived with a vengeance. In this uncertain and dangerous time,

Elsa Martinelli—like so many of her neighbors—must make an agonizing choice: fight for the land she loves or go west, to California, in search of a better life. The Four Winds is an indelible portrait of America and the American Dream, as seen through the eyes of one indomitable woman whose courage and sacrifice will come to define a generation.

OR you could read this classic…

The most interesting figure of this Oklahoma family is the son who has just been released from jail. He is on his way home from prison, hitch-hiking across the State in his new cheap prison suit, picking up a preacher who had baptized him when young, and arriving to find the family setting out for California. The Bank had come “to tractorin’ off the place.” The house had been knocked over by the tractor making straight furrows for the cotton. The Joad family had read handbills promising work for thousands in California, orange picking. They had bought an old car, were on the point of leaving, when Tom turned up from prison with the preacher. They can scarcely wait for this promised land of fabulous oranges, grapes and peaches. Only one stubborn fellow remains on the land where his great-grandfather had shot Indians and built his house. The others, with Tom and the preacher, pack their belongings on the second-hand truck, set out for the new land, to start over again in California.

Nonfiction

The “dust bowl” of the 1930s covered 100 million acres spread over five states: Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, Nebraska and Colorado. From 1930 to 1935, nearly a million people left their farms, littered with animal corpses and stunted crops. Schools closed. Towns simply disappeared. Thousands died from “dust pneumonia,” a new condition born of swallowing and inhaling the swirling topsoil. The author personalizes this tragedy by focusing on a handful of hardy settlers who came to America’s heartland with high hopes and boundless energy, then watched with growing despair as the earth turned against them. In truth, the dust bowl was largely a human creation. The great southern plains, once covered with native grasses that fed the buffalo and held the soil in place, were essentially stripped bare in the 1920s by wheat-farmers eager to cash in on cheap land and high grain prices.

Selections for Wednesday, February 12th at 7:30

Climate Change

Fiction

In the wrong hands, fiction written to convey urgent social messages is as tedious as a political harangue. But done well, it can be both eye-opening and moving: think Charles Dickens on children and poverty in Oliver Twist; Upton Sinclair on the meat-processing industry in The Jungle; Toni Morrison on the tolls of slavery in Beloved; E.L. Doctorow on the collateral damage of war in The March.

While Kingsolver’s seventh novel, Flight Behavior, does not quite achieve the resonance of Morrison’s and Doctorow’s masterpieces, this is partly due to its inherently less dramatic material. What it shares with these books is an integration of important issues with engaging narrative that feels organic: A colony of butterflies and a young woman have both deviated from their optimal flight paths, a story Kingsolver uses to take on global warming and the high costs to society of grossly inadequate public school education, especially in the sciences.

But, as readers of The Poisonwood Bible and The Lacuna are well aware, Kingsolver is no mere propagandist. She is a storyteller first and foremost, as sensitive to human interactions and family dynamics as she is to ecological ones.

Nonfiction

The human animal knows that it is born to age and die. Together with language, this knowledge is what separates us from all other species. Yet, until the 18th century, not even Aristotle, who speculated about most things, actually considered the possibility of extinction.

This is all the more surprising because “the end of the world” is an archetypal theme with a sonorous label – eschatology – that morphs in popular culture into many doomsday scenarios, from global warming to the third world war. Citizens of the 21st century now face a proliferating menu of possible future dooms.

Elizabeth Kolbert’s The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History is both a highly intelligent expression of this genre and also supremely well executed and entertaining. Her book, which follows her global warming report Field Notes from a Catastrophe (2006), is already set to become a contemporary classic, and an excellent place to start this new series of landmark nonfiction titles in the English language.

Selections for Wednesday, January 8th at 7:30

New York

Fiction

Deacon King Kong is fast, deep, complex, and hilarious. McBride’s prose is shimmering and moving, a living thing that has its own rhythm, pulls you in from the first page and never lets go. His story focuses on the people that make the Big Apple what it is: the strange, the poor, the insane, the mobsters. He also showcases the city’s wonderful diversity, filling his pages with Puerto Ricans, African Americans, Italians, and Irish folks.

And all these many people get a turn in the spotlight. Sportcoat is at the center of everything, but folks from church and the projects, small time crooks, bodega owners, mobsters, and cops all get space on the page, and they all earn it. McBride has a talent for writing about big ensembles, and here even the city and its animals are important players.

Nonfiction

New York journalist Mahler vividly recalls the Big Apple’s spirit of ’77 (though he was only eight and living in California at the time). The city was in a fiscal crisis, with doom, ruin, and Rupert Murdoch pressing forward. There were subway strikes, garbage strikes, and job actions by the city’s finest—the police. President Gerald Ford, according to the headlines, invited the metropolis to drop dead. An emergent gay scene, punk rock, Studio 54 (“a fifty-four-hundred-square-foot dance floor crowded with undulators, balconies crowded with fornicators”), and diverse raunchy venues like Plato’s Retreat marked New York’s special culture. Then, in the sweltering midsummer, came Con Ed’s great power blackout, followed by rioting and looting throughout the five boroughs. The newspapers delighted in indigenous characters named Bella Abzug, John Lindsay, Abe Beame, Albert Shanker, and Son of Sam. The epic campaign for the mayor’s slot on the Democratic ticket boiled down to Messrs. Koch and Cuomo. Meanwhile, the ineffable Yankees contended with their own epic battle between belligerent manager Billy Martin and self-important slugger Reggie Jackson. And, most cleverly, Mahler devotes a major portion of this chronicle to the period’s baseball history. Despite the odds against such a combination being successful, he pulls off an expert historical double play by blending front-page political news and sports-page action.

Selections for Wednesday, December 11th at 7:30

Dances with Cephalopods

Fiction

Van Pelt, a former financial consultant, first had the idea that morphed into the novel in 2013, when she took a fiction writing workshop at Emory University in Atlanta. One of the assignments was to write a short story from an unusual perspective, and she came up with an acerbic octopus who was bored and frustrated by his confinement in an aquarium. Her teacher pulled her aside and suggested she build something larger around the character, and she began writing vignettes about the octopus.

At first, she didn’t worry too much that she was taking a creative risk by having a highly intelligent octopus narrator and protagonist, because she didn’t think her work would ever get published. “I wasn’t thinking too hard about, is this salable?” she said, “because I never thought anybody would read it.”

She kept toying with the character and eventually saw the potential for a novel, but realized it would be difficult to sustain an entire book from an octopus’s perspective. She came up with Tova, a 70-year-old widow with a painful past who works as a cleaner at an aquarium. The story is set in a fictional town in the Pacific Northwest, where Van Pelt grew up; Tova is based on Van Pelt’s stoic Swedish grandmother.

Nonfiction

In this astonishing book from the author of the bestselling memoir, The Good Good Pig, Sy Montgomery explores the emotional and physical world of the octopus—a surprisingly complex, intelligent, and spirited creature—and the remarkable connections it makes with humans.

Sy Montgomery’s popular 2011 ORION magazine piece, “Deep Intellect,” about her friendship with a sensitive, sweet-natured octopus named Athena and grief at her death, went viral, indicating the widespread fascination with these mysterious, almost alien-like creatures. Since then she has practiced true immersion journalism, from New England aquarium tanks to Mexico and French Polynesia, pursuing these solitary shape-shifters. With a central brain the size of that of an African grey parrot and neural matter in each of its eight arms, octopuses have varied personalities and intelligence they show in myriad ways: endless trickery to get food and escape enclosures; jetting water playfully to bounce objects like balls; and evading their caretakers by using a scoop net as a trampoline and running around the floor on eight arms. But with a beak like a parrot, venom like a snake, and a tongue covered with teeth, how can such a being know anything?

Selections for Wednesday, November 13th at 7:30

Poverty

Fiction

Demon Copperhead re-envisions the Charles Dickens classic David Copperfield, setting it in modern-day Appalachia. Kingsolver conceived the idea while on a visit to Dickens’s historic seaside English retreat and actually started writing Demon Copperhead at Dickens’s own desk. It’s Kingsolver’s 17th novel in some three decades, and in writing it, she says she wanted to counter some of the condescension and downright snobbery directed at the region in which she was born and still lives, an area whose people, she believes, have been exploited for generations, most recently by pharmaceutical companies who targeted Appalachian residents and created the current opioid crisis. As Kingsolver recently told The New York Times, this produced “a generation of kids who’ve had their lives torn apart.”

Nonfiction

Desmond shows that poverty blights rural white areas but that its hardest core is African American and urban. Having written the entry on racial capitalism for the New York Times 1619 project, Desmond is sensitive to the way poverty intersects other forms of subordination. Another sociologist, the great William Julius Wilson, argued more than three decades ago that deindustrialisation was to blame for African American impoverishment, by depriving men of good manufacturing jobs. But Desmond thinks this thesis, while accurate, misses the various ways in which “the rich keep the poor down for their own benefit”. Sociologists, Desmond charges, have shied away from “empirical studies of power and exploitation”. Politicians and well-meaning observers have wrung their hands without facing the “uncomfortable” possibility that the poor remain so because the wealthier want it that way.

Selections for Wednesday, October 9th at 7:30

The Death of Critical Thinking

Fiction

President of the United States Donald Vanderdamp is having a hell of a time getting his nominees appointed to the Supreme Court. After one nominee is rejected for insufficiently appreciating To Kill A Mockingbird, the president chooses someone so beloved by voters that the Senate won’t have the guts to reject her — Judge Pepper Cartwright, the star of the nation’s most popular reality show, Courtroom Six.

Will Pepper, a straight-talking Texan, survive a confirmation battle in the Senate? Will becoming one of the most powerful women in the world ruin her love life? And even if she can make it to the Supreme Court, how will she get along with her eight highly skeptical colleagues, including a floundering Chief Justice who, after legalizing gay marriage, learns that his wife has left him for another woman. Soon, Pepper finds herself in the middle of a constitutional crisis, a presidential reelection campaign that the president is determined to lose, and oral arguments of a romantic nature. Supreme Courtship is another classic Christopher Buckley comedy about the Washington institutions most deserving of ridicule.

Nonfiction

For fifteen years, bestselling author Michael Shermer has written a column in Scientific American magazine that synthesizes scientific concepts and theory for a general audience. His trademark combination of deep scientific understanding and entertaining writing style has thrilled his huge and devoted audience for years. Now, in Skeptic: Viewing the World with a Rational Eye, seventy-five of these columns are available together for the first time; a welcome addition for his fans and a stimulating introduction for new readers.

Selections for Wednesday, September 11th at 7:30

Science & Ethics of Genetics

Fiction

Kazuo Ishiguro’s “Never Let Me Go” (Knopf; $24) is a novel about a young woman named Kathy H., and her friendships with two schoolmates, Ruth and Tommy. The triangle is a standard one: Kathy is attracted to Tommy; Tommy gets involved with Ruth, who is also Kathy’s best friend; Ruth knows that Tommy is really in love with Kathy; Kathy gets Tommy in the end, although they both realize that it is too late, and that they have missed their best years. Their lives are short; they know that they are doomed. So the small betrayal leaves an enormous wound. As is customary with Ishiguro, the narrator, Kathy, is ingenuous but keenly desirous of telling us how it was, the prose feels self-consciously stilted and banal, and the psychology is not deep. The central premise in this book is basically the same as that in the book that made Ishiguro famous, “The Remains of the Day” (1989): even when happiness is standing right in front of you, it’s very hard to grasp. Probably you already suspected that.

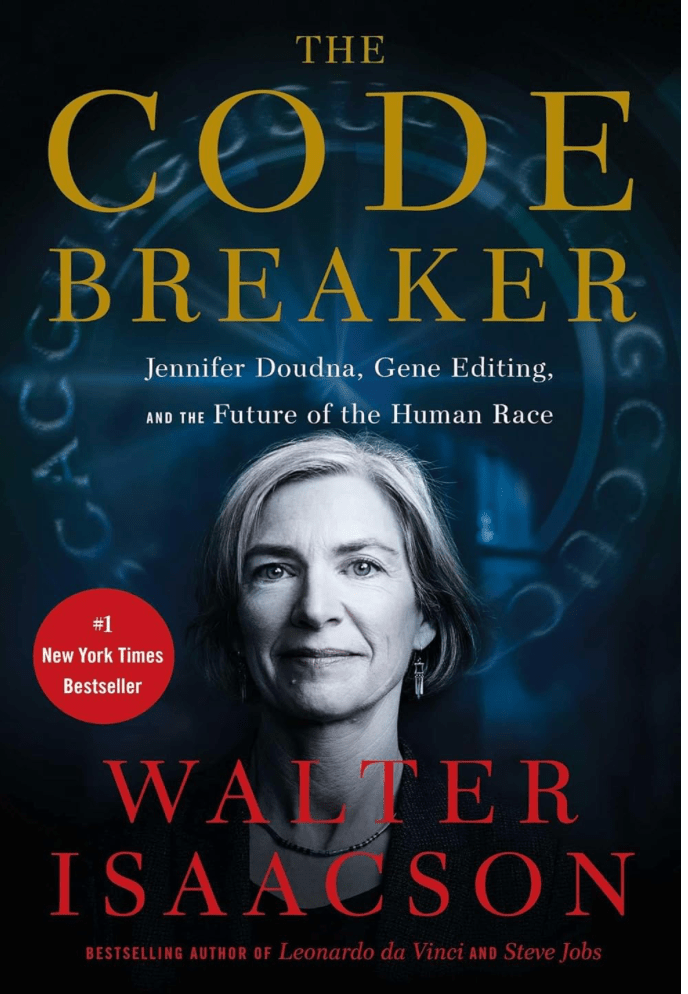

Nonfiction

Genetic destiny is a central theme of The Code Breaker, Isaacson’s portrait of the gene-editing pioneer Jennifer Doudna, who, with a small army of other scientists, handed humanity the first really effective tools to shape it. Rufus Watson’s reflections encapsulate the ambivalence that many people feel about this. If we had the power to rid future generations of diseases such as schizophrenia, would we? The immoral choice would be not to, surely? What if we could enhance healthy human beings, by editing out imperfections? The nagging worry – which might one day seem laughably luddite, even cruel – is that we would lose something along with those diseases and imperfections, in terms of wisdom, compassion and, in some way that is harder to define, humanity.