Selections for Wednesday, June 12th at 7:30

Hollywood

Fiction

Monique Grant is stunned when Hollywood legend Evelyn Hugo grants an exclusive interview to her over more seasoned journalists, but when she’s also chosen to publish Evelyn’s final confessions after her death, she learns that the 79-year-old actress has enough life experience for them both. Growing up poor in Hell’s Kitchen, young Evelyn Herrera trades her virginity for a ride to Hollywood, changes her name, and climbs the rungs of the entertainment-industry ladder one husband at a time until she hits Oscar gold. To write her off as being calculating and fickle would leave out the difficulty of being a woman, especially a woman of color, trying to get by in the late 1950s without a man’s blessing. Evelyn plays up her bombshell figure and hides her Cuban roots by dying her hair blonde—the first of many lies she’ll have to tell over the course of her life to prove to the world that she deserves her place in the spotlight.

She’s unapologetically ambitious but not without remorse. Which of her seven husbands was her true love? Why did she choose Monique to tell her story? Evelyn recounts her failures and triumphs in chronological order, one husband at a time, with a few breaks for Monique to report back to her editor. The celebrity tell-all style is a departure from Reid’s (One True Loves, 2016, etc.) previous books, but Evelyn Hugo is a character who can demand top billing. When asked if it bothers her that “all anyone talks about when they talk about you are the seven husbands of Evelyn Hugo,” she says no: “Because they are just husbands. I am Evelyn Hugo.”

Nonfiction

This is at least the fourth book to be written about a murder that, unless you’re a silent-movie buff, you’ve probably never heard of. On the morning of Feb. 2, 1922, William Desmond Taylor, one of Hollywood’s leading directors, was found lying on the floor of his apartment, dead from a bullet to the chest. Although the case became a national sensation, it was never solved.

A more famous director, King Vidor, took an interest in the murder and collected all the information he could. In 1986, Sidney D. Kirkpatrick relied on Vidor’s archive to crack the case to his own satisfaction in a book called “A Cast of Killers.” Four years later, convinced that Kirkpatrick had gotten it wrong, the eminent publisher Robert Giroux played amateur detective in his book “A Deed of Death.” And in 2004, the prolific Charles Higham weighed in with “Murder in Hollywood.” Each author gave a different answer to the question of whodunit.

Now comes William J. Mann, who previously has written biographies of Katharine Hepburn and Barbra Streisand. Relegating the word “murder” to the subtitle, Mann calls his treatment of the case “Tinseltown.” As the reader soon learns, Mann thinks that to solve Taylor’s murder, we must pay close attention to what the film industry was going through in the early 1920s, and his dragnet encompasses “characters” including film mogul Adolph Zukor, comedian Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle, movie censor Will Hays, three young actresses, some gangsters, an ambitious stage mother and a cadre of what Mann calls “church ladies.”

Selections for Wednesday, May 8th at 7:30

100 Years of Midwest in the U.S.

Fiction

An award-winning author for his long-running Cork O’ Connor series (Trickster’s Point, 2012, etc.), Krueger aims higher and hits harder with a stand-alone novel that shares much with his other work. The setting is still his native Minnesota, the tension with the region’s Indian population remains palpable and the novel begins with the discovery of a corpse, that of a young boy who was considered a little slow and whose body was found near the train trestle in the woods on the outskirts of town. Was it an accident or something even more sinister? Yet, that opening fatality is something of a red herring (and that initial mystery is never really resolved), as it serves as a prelude to a series of other deaths that shake the world of Frank Drum, the 13-year-old narrator (occasionally from the perspective of his memory of these events, four decades later), his stuttering younger brother and his parents, whose marriage may well not survive these tragedies. One of the novel’s pivotal mysteries concerns the gaps among what Frank experiences (as a participant and an eavesdropper), what he knows and what he thinks he knows. “In a small town, nothing is private,” he realizes. “Word spreads with the incomprehensibility of magic and the speed of plague.” Frank’s father, Nathan, is the town’s pastor, an aspiring lawyer until his military experience in World War II left him shaken and led him to his vocation. His spouse chafes at the role of minister’s wife and doesn’t share his faith, though “the awful grace of God,” as it manifests itself within the novel, would try the faith of the most devout believer. Yet, ultimately, the world of this novel is one of redemptive grace and mercy, as well as unidentified corpses and unexplainable tragedy.A novel that transforms narrator and reader alike.

More fiction

“O Pioneers!” concerns Swedish immigrants. We see their plight in the very first words of the novel:

One January day, thirty years ago, the little town of Hanover, anchored on a windy Nebraska tableland, was trying not to be blown away.… The dwelling houses were set about haphazard on the tough prairie sod; some of them looked as if they had been moved in overnight, and others as if they were straying off by themselves, headed straight for the open plain. None of them had any appearance of permanence, and the howling wind blew under them as well as over them.

The wind blew under the houses. It’s like “The Wizard of Oz.”

As the first chapter opens, a five-year-old boy, Emil Bergson, is crying his eyes out. He and his older sister—Alexandra, twenty years old—have come into town to get supplies. Alexandra dotes on Emil, and she let him bring his kitten with him. Now, a dog has chased the kitten up a telegraph pole, where she is freezing, but she won’t come down. A friend of Alexandra’s, Carl Linstrum, hikes up the pole and rescues the kitten. Other animals in “O Pioneers!” are not so lucky, nor are the human beings.

April 10, 2024: Implications of Passing

Fiction

The little-known story of the Black woman who supervised J. Pierpont Morgan’s storied library.

It’s 1905, and financier J.P. Morgan is seeking a librarian for his burgeoning collection of rare books and classical and Renaissance artworks. Belle da Costa Greene, with her on-the-job training at Princeton University, seems the ideal candidate. But Belle has a secret: Born Belle Marion Greener, she is the daughter of Richard Greener, the first Black graduate of Harvard, and she’s passing as White. Her mother, Genevieve, daughter of a prominent African American family in Washington, D.C., decided on moving to New York to live as White to expand her family’s opportunities. Richard, an early civil rights advocate, was so dismayed by Genevieve’s decision that he left the family. As Belle thrives in her new position, the main source of suspense is whether her secret will be discovered.

Nonfiction

To be black but to be perceived as white is to find yourself, at times, in a racial no man’s land. It is to feel like an embodiment of W. E. B. Du Bois’s double consciousness — that sense of being in two places at the same time. It is also to be perpetually aware of both the primacy of race and the “bankruptcy of the race idea,” as Allyson Hobbs, an assistant professor of history at Stanford University, puts it in her incisive new cultural history, “A Chosen Exile.”

Hobbs is interested in the stories of individuals who chose to cross the color line — black to white — from the late 1800s up through the 1950s. It’s a story we’ve of course read and seen before in fictional accounts — numerous novels and films that have generally portrayed mixed-race characters in the sorriest of terms. Like gay characters, mulattoes always pay for their existence dearly in the end. Joe Christmas, the tormented drifter in William Faulkner’s “Light in August,” considers his blackness evidence of original sin (a.k.a. miscegenation) and ends up castrated and murdered. Sarah Jane, a character in Douglas Sirk’s 1959 remake of the film “Imitation of Life,” denies her black mother in her attempt to be seen as white. Her tragedy once again feels like mixed fate. As her long-suffering mother puts it, “How do you tell a child that she was born to be hurt?”

March 13, 2024: Capitalism

Fiction

The museum of the novel’s title is a Coney Island boardwalk attraction presided over by Professor Sardie, part mad scientist and part shrewd magician. Adjacent to Luna Park, the Steeplechase and the soon-to-open Dreamland, this showcase of “living wonders” has at various times over the years included the Wolfman, the Butterfly Girl, the Goat Boy, the Bird Woman, the Bee Woman and the Siamese Twins, along with a menagerie of frogs, vipers, lizards, hummingbirds, a 100-year-old tortoise — and Sardie’s daughter, Coralie, who has, from the age of 10, spent hours suspended in a tank of water playing the Human Mermaid for paying customers. (As she grows older, her sinister father compels her to perform lewd after-hours displays for a select audience of patrons willing to pay a premium.)

Nonfiction (option 1)

Ahab and the Great White Whale. Sisyphus and the boulder. Charley Brown and the football. The attempt to write the Big Book of Progressivism–the single volume that synthesizes the most amorphous period in American history–is rapidly on its way to joining these other metaphors for the maddeningly unachievable quest. The length of the list of gifted historians who have attempted syntheses of late-nineteenth and early-twentieth-century America is matched only by the critiques of these same histories. Despite this criticism, historians’ attempts to define the Progressive movement have invariably enriched our understanding of the period. And Michael McGerr’s A Fierce Discontent: The Rise and Fall of the Progressive Movement in America 1870-1920 should find its place alongside The Age of Reform, The Search for Order, The Triumph of Conservatism, and other valuable, intriguing, and ultimately well-critiqued big books on Progressivism.

Nonfiction (option 2)

How the Other Half Lives was a pioneering work of photojournalism by Jacob Riis, documenting the squalid living conditions in New York City slums in the 1880s. It served as a basis for future muckraking journalism by exposing the slums to New York City’s upper and middle class. How The Other Half Lives quickly became a landmark in the annals of social reform. Riis documented the filth, disease, exploitation, and overcrowding that characterized the experience of more than one million immigrants. He helped push tenement reform to the front of New York’s political agenda, and prompted then-Police Commissioner Theodore Roosevelt to close down the police-run poor houses. Roosevelt later called Riis “the most useful citizen of New York”. Riis’s idea inspired Jack London to write a similar exposé on London’s East End, called People of the Abyss.

February 24, 2024: Baltimore

Fiction

The story told in Lady in the Lake began, in many ways, five decades before the book’s release, in 1969. In June of that year, the body of Shirley Lee Wigeon Parker, a black 35-year-old divorcee, was found in a fountain in one of the city’s parks. About three months later, in September, Esther Lebowitz, an 11-year-old Jewish girl, was beaten to death inside a fish store, in a gruesome, traumatising killing that profoundly impacted Baltimore’s Jewish community.

Those two stories collide in Lady in the Lake when Maddie Schwartz, a freshly divorced, 37-year-old former housewife, encounters the body of a recently murdered schoolgirl called Tessie Fine (whose story mirrors Esther Lebowitz’s). Maddie, who needs a job and, more importantly, a new identity besides being her husband’s former wife, turns the incident first into a story, then lands herself a bottom-of-the-ladder job at the fictional (but delightfully realistic) Baltimore Star….What follows is the tale of Maddie’s dogged determination to find out what happened to Cleo in the days before her death, and her equally staunch desire to carve herself a spot at the newspaper.

Nonfiction

An incomparable, epic nonfiction police procedural, covering one year with a Baltimore homicide squad—and a dizzying circus of mayhem and stark horror at vast length. Simon, a police reporter for the Baltimore Sun, spent 1988 as a fly on the wall with Baltimore’s homicide unit. Here, he tells what it was like to investigate dozens of Baltimore’s 234 murders that year. We follow three homicide squads from first alert by phone to arrival at the body, through first investigation of the crime scene, questioning of witnesses, and writing up reports back at the police department. Subjectively, however, we are right over the shoulder of the investigating detectives, sharing their horrifying safety-valve humor in the face of headless suicides, bullet-riddled corpses, a gutted 11- year-old girl and so on. This story is about turning over rocks on rock bottom and looking for what squirms. Murderers, it turns out, don’t act like they do on TV—nor do the detectives: with the exception of suspects who kill loved ones in a rage, killers are utterly remorseless, and whatever stress they feel is tied to being the target of an investigation.

January 10, 2024: Earth-shattering Works

Fiction

Early on in the novel’s more than six-year composition process, Ellison discarded the dominant literary modes among Black writers at the time: naturalism (the idea that environment is determinant of human character) and realism (the effort to represent on the page lived experience in concrete terms), both powerfully exemplified in his friend Richard Wright’s 1940 classic, “Native Son.” That kind of fiction, Ellison believed, was too restrictive to capture the raucous humor, the quality of intellect and the improvisational spirit of his protagonist. He also resisted, and perhaps resented, the impulse of many white critics and readers to confuse Black fiction with sociology. With “Invisible Man,” Ellison set out to write a novel that would be impossible simply to file and forget.

Nonfiction

If volcanoes make you giddy, then this is the book for you. Robin George Andrews is that rare hybrid of the scientist–journalist: a volcanologist who decided to focus on science communication after completing his PhD. Super Volcanoes combines scientific exactitude with engaging writing and is a tour of some exceptional volcanoes on Earth and elsewhere in the Solar System. Andrews starts it with an unabashedly enthusiastic mission statement: “I want you to feel unbridled glee as these stories sink in and an indelible grin flashes across your face as you think: holy crap, that’s crazy!” (p. xxi). For me, he nailed it and I found this an incredibly satisfying read.

December 13, 2023: Civil War

Fiction

From Louisa May Alcott’s beloved classicLittle Women, Geraldine Brooks has taken the character of the absent father, March, who has gone off to war, leaving his wife and daughters to make do in mean times. To evoke him, Brooks turned to the journals and letters of Bronson Alcott, Louisa May’s father–a friend and confidant of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau. In her telling, March emerges as an idealistic chaplain in the little known backwaters of a war that will test his faith in himself and in the Union cause as he learns that his side, too, is capable of acts of barbarism and racism. As he recovers from a near mortal illness, he must reassemble his shattered mind and body and find a way to reconnect with a wife and daughters who have no idea of the ordeals he has been through.

Nonfiction

Most Americans know the traditional story of Ulysses S. Grant (1822-1885): a modest but brutal general who pummeled Robert E. Lee into submission and then became a bad president. Historians changed their minds a generation ago, and acclaimed historian Chernow (Washington: A Life, 2010, etc.), winner of both the National Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize, goes along in this doorstop of a biography, which is admiring, intensely detailed, and rarely dull. A middling West Point graduate, Grant performed well during the Mexican War but resigned his commission, enduring seven years of failure before getting lucky. At the outbreak of the Civil War, he was the only West Point graduate in the area, so local leaders gave him a command. Unlike other Union commanders, he was aggressive and unfazed by setbacks. His brilliant campaign at Vicksburg made him a national hero. Taking command of the Army of the Potomac, he forced Lee’s surrender, although it took a year. Easily elected in 1868, he was the only president who truly wanted Reconstruction to work.

November 8, 2023: Visions of the Future

Fiction

“Parable of the Sower” unfolds through the journal entries of its protagonist, a fifteen-year-old black girl named Lauren Oya Olamina, who lives with her family in one of the walled neighborhoods. “People have changed the climate of the world,” she observes. “Now they’re waiting for the old days to come back.” She places no hope in Donner, whom she views as “a symbol of the past to hold onto as we’re pushed into the future.” Instead, she equips herself to survive in that future. She practices her aim with BB guns. She collects maps and books on how Native Americans used plants. She develops a belief system of her own, a Darwinian religion she names Earthseed. When the day comes for her to leave her walled enclave, Lauren walks west to the 101 freeway, joining a river of the poor that is flooding north. It’s a dangerous crossing, made more so by a taboo affliction that Lauren was born with, “hyperempathy,” which causes her to feel the pain of others.

Nonfiction

In Saving Us, Hayhoe argues that when it comes to changing hearts and minds, facts are only one part of the equation. We need to find shared values in order to connect our unique identities to collective action. This is not another doomsday narrative about a planet on fire. It is a multilayered look at science, faith, and human psychology, from an icon in her field—recently named chief scientist at The Nature Conservancy.

Drawing on interdisciplinary research and personal stories, Hayhoe shows that small conversations can have astonishing results. Saving Us leaves us with the tools to open a dialogue with your loved ones about how we all can play a role in pushing forward for change.

October 11, 2023: Lincoln

Fiction

“In this, his first novel, the Lincoln trapped in the bardo is Willie, the cherished 11-year-old son of the great civil war president. As his parents host a lavish state reception, their boy is upstairs in the throes of typhoid fever. Saunders quotes contemporary observers on the magnificence of the feast, trailing the terrible family tragedy that is unfolding. Sure enough, Willie dies and is taken to Oak Hill cemetery, where he is interred in a marble crypt. On at least two occasions – and this is the germ of historical fact from which Saunders has spun his extraordinary story – the president visits the crypt at night, where he sits over the body and mourns.”

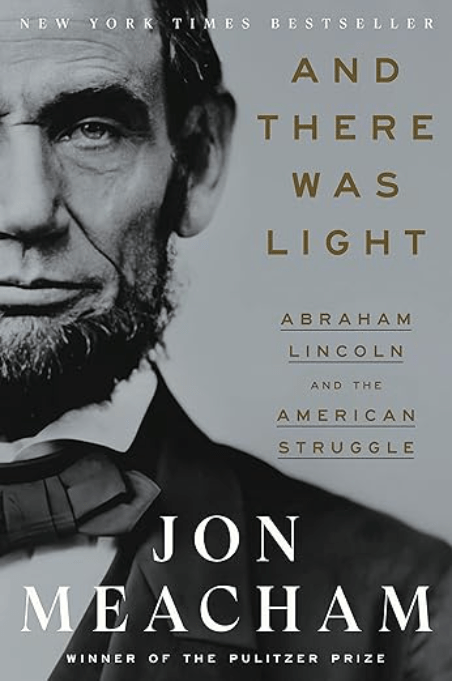

Nonfiction

“Every generation gets its own Abraham Lincoln biography. But if time seems to move faster these days, then perhaps it is altogether fitting and proper that our generation should have so many. The latest — Pulitzer Prize winner Jon Meacham’s “And There Was Light: Abraham Lincoln and the American Struggle” —offers an account of the life of the United States’ 16th president that is worldly and spiritual, and carefully tailored to suit our conflict-ridden times.

Meacham bids to be the redeemer in chief of the narrative of American exceptionalism: the venerable if now-shopworn story in which the United States has a providential and world-historic role as a nation distinctively dedicated to human liberty. He is almost certainly the most well-connected presidential biographer of the moment. His 2008 biography of Andrew Jackson, “American Lion,” won a Pulitzer Prize for balancing Jackson’s many faults, including his relentless efforts to destroy Native American Indian tribes, with his success in holding together a country whose “protections and promises,” as Meacham asserted, eventually extended to all. Meacham’s 2015 biography of George H.W. Bush, “Destiny and Power,” maintained a respectable critical distance while treating his subject with sufficient dignity that the Bush family asked him to deliver the eulogy at the National Cathedral. His 2018 book “The Soul of America,” a spirited defense of the promise of America for the Trump years, captured the attention of Joe Biden, who used the title as a catch phrase in his 2020 presidential campaign while relying on Meacham for speechwriting counsel.”